So this newsletter doesn’t want to be an omnicomprehensive look on the role of architecture in Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira. The research is still work in progress. Let’s say this is an intermediate point (maybe 1/3), where we see some material, discuss hypothesis, lucubrate on the references and (mostly) enojoy great (great) images.

[Your e-mail provider will probably chunk this mail (since is too long), be sure to click continue at the end of it.]

Today’s newsletter will not have the usual structure. It will be similar to a past newsletter dedicated to the architecture of the manga Berserk by Kentaro Miura. My name is Federico and welcome to Representations of Architecture #36.

History of the Manga

Most of you will probably familiar with the anime movie Akira (1988)1. Directed by Katsuhiro Otomo himself, the movie is a masterpiece of modern animation but, as usually happen in Japan, it is an adaptation of the manga2.

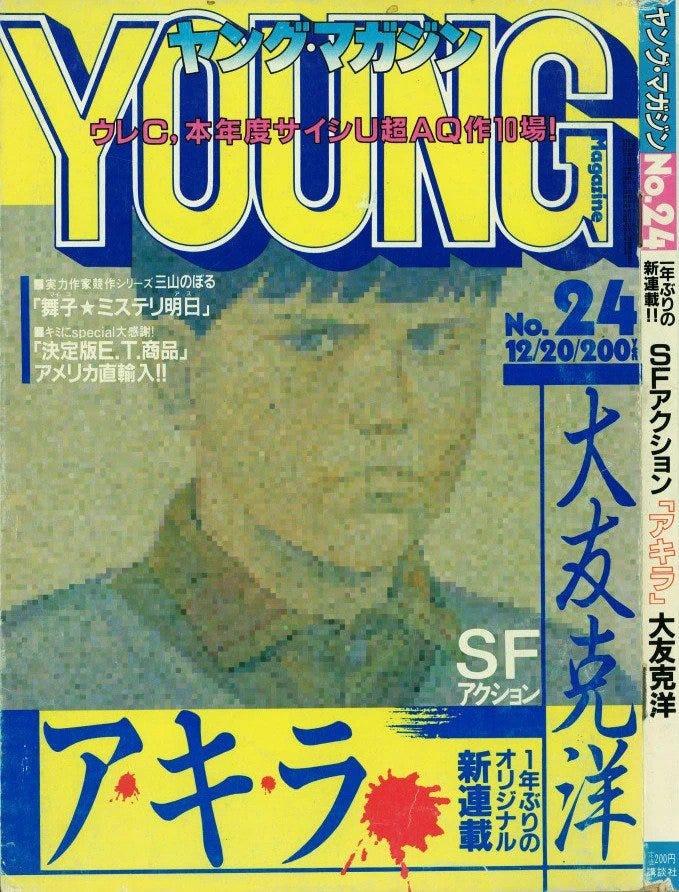

Akira was first published on Young Magazine, a 300+ pages weekly magazine by Kodansha collecting episodes from different manga series. The first episode was published in December 1982: the rest is history. Akira saw a growing number of fans, becoming in just a couple of years one of the most famous mangas serialized.

But what are the reasons behind his great success? Let’s list them:

Compelling Story: Kaneda, the leader of a bikers gang, has to save his best friend Tetsuo from self-destruction while preventing the awake of Akira, a psychic-powered human weapon that already destroyed Tokyo 30 years before. A reductive summarization of a story characterized by multiple nouances and sub-plot lines.

The shaping of the Cyberpunk aesthetics: The first chapter was released the same year of Blade Runner, and that’s no coincidence. Akira with its wild aesthetic and urban scenarios created a new standard in the depiction of what is today recognized as Cyberpunk.

Aura of coolness: Every little feature of Akira is sorrounded by a thin film of coolness. The clothing, the vehicles, the settings, the framing, the rhytm, the dialogues, the architectures. Every aspect of Akira is so well conceived that became an instant classic.

Incredible drawings: Last but not least, the amazing art by Katsuhiro Otomo and his assistants. In Akira, Otomo is able to deploy an arsenal of solutions gained in the previous 10 years of activity.

This last point prompt us to talk about what we are here for: Akira’s Architecture.

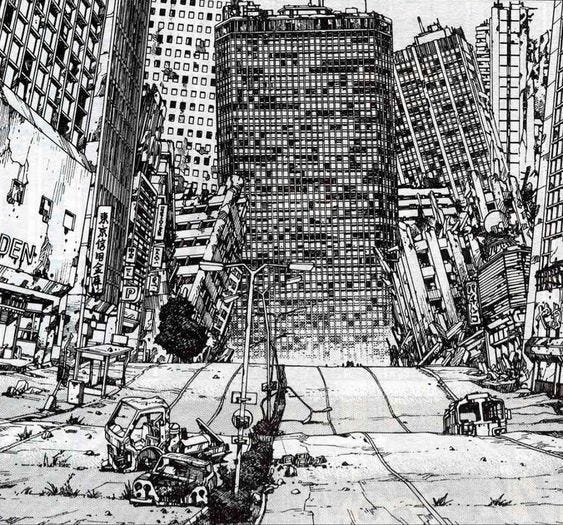

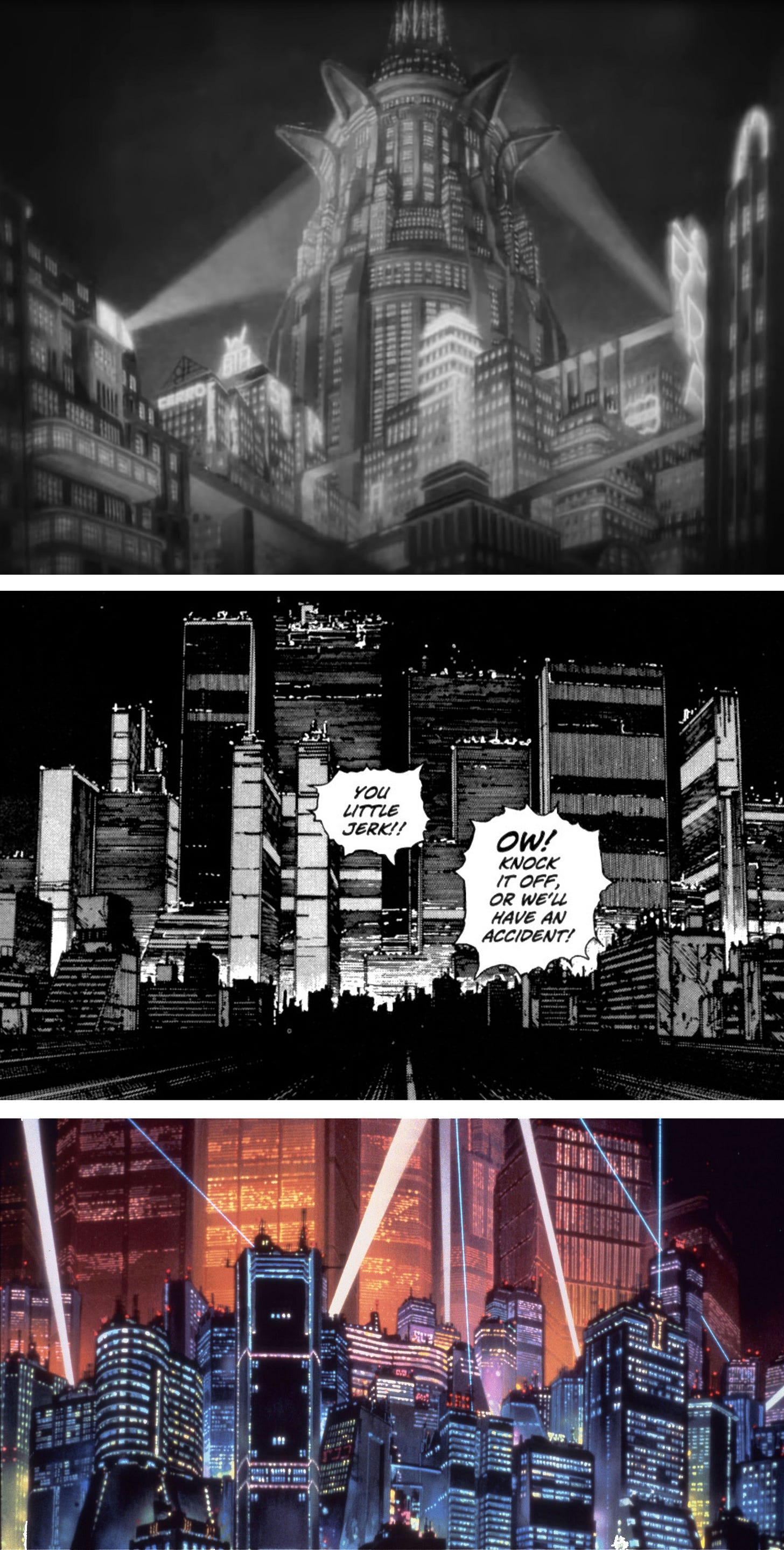

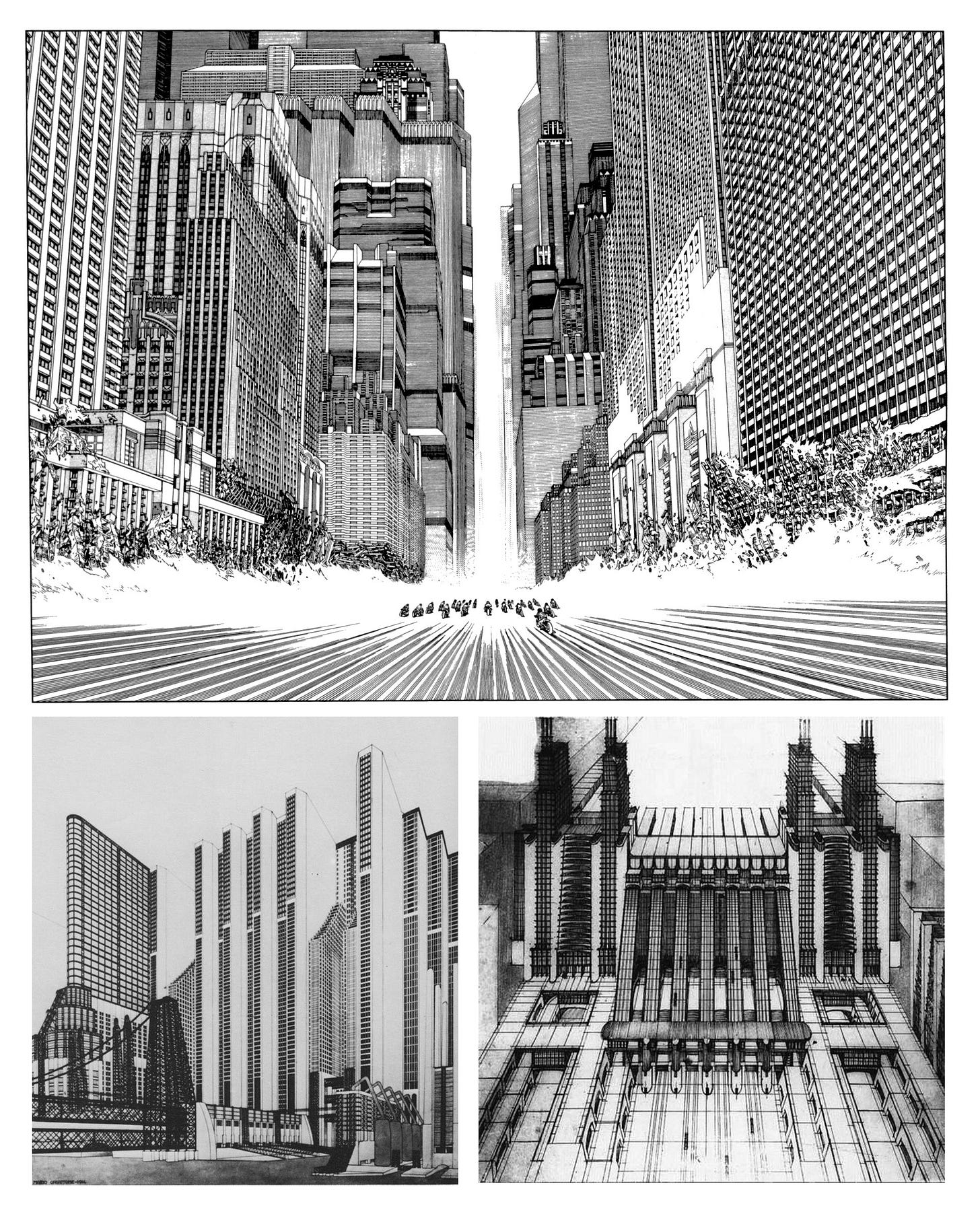

One of the things that made me love the manga so much was its scenario: Neo-Tokyo. Its scale is non-human. Neverending skyscrapers loom on the streets were bikers and punks wander around. Neon lights illuminate a city filled with corruption, protests and violence. An high-tech city that gives the impression of being the fruit of an exaggerated expansion, on the edge of an imminent collapse.

References

Neo-Tokyo was not born out of the blue. Otomo imagined it thanks to the frenetic japanese urban expansion of those years, Tokyo’s expansion specifically. As we saw in a past newsletter, japanese cities were not so developed in height before 19633. As it became possible to develop buildings in height, more and more skyscrapers began to be erected. The large construction corporations were changing the Japanese ground, in line with a thriving economy and population growth.

Otomo's Neo-Tokyo is therefore the exasperation of the immoderate growth that the mangaka was witnessing in those years. He simply imagined what (almost) likely could have happened 40 years from now.

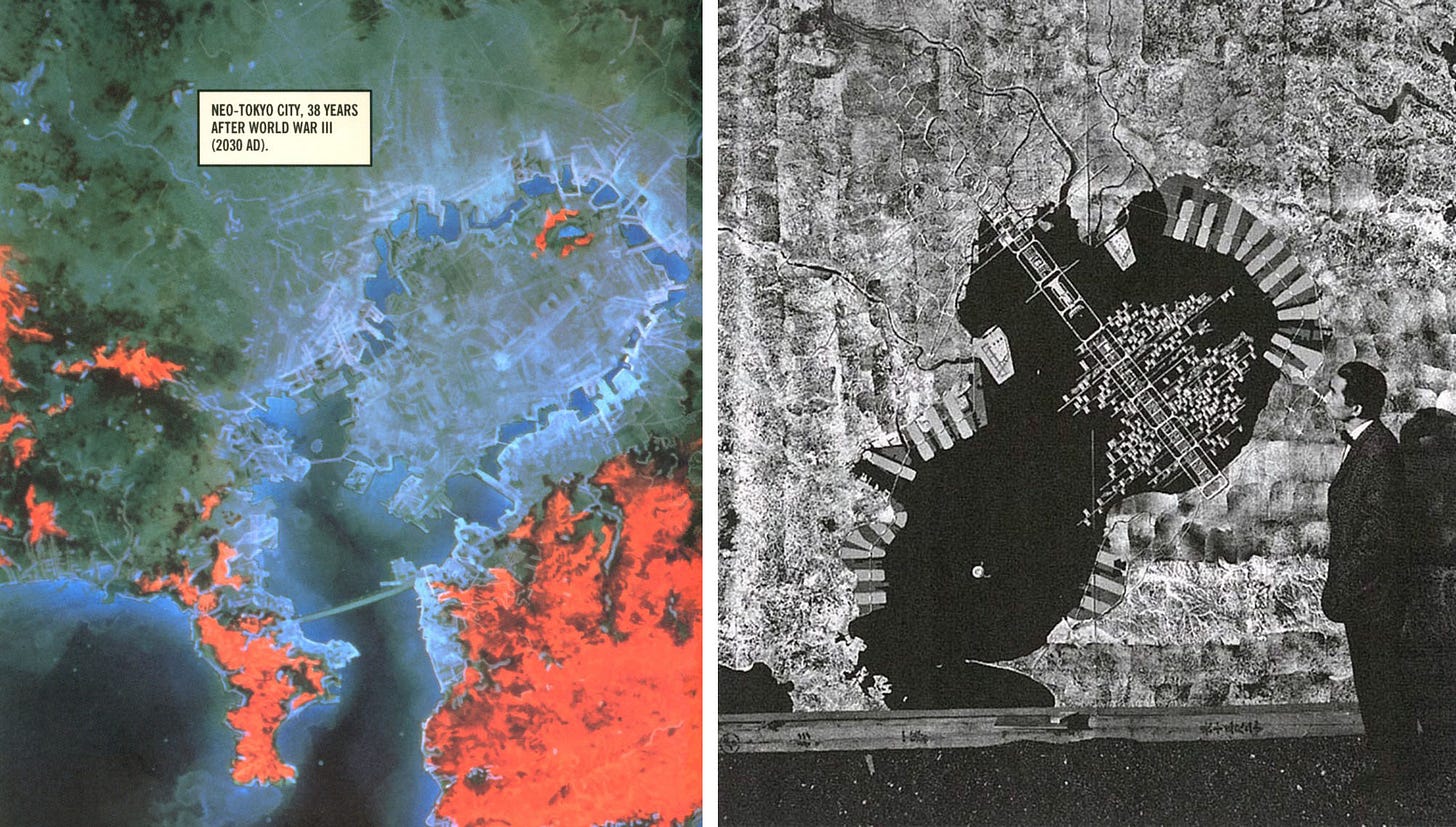

Akira's story is in fact set in 2019. 38 years have passed since a mysterious explosion destroyed almost all of Tokyo. The city was rebuilt into a high-tech megalopolis. It was not rebuilt in the area of the explosion, but rather somewhere else: in the bay.

Here we find the first major connection with the world of architecture. The colonization of Tokyo Bay is exactly the famous project A Plan for Tokyo 1960 by Kenzo Tange. An idea that never became a reality but which had an important media coverage4, evidently remaining impressed in Otomo's mind.

Neo-Tokyo is an out-of-scale city. Exaggerated perspectives from below amplify its height, with skyscrapers that stack on top of each other in a disorderly but scenographic way. In fact, with respect to the observer, they behave exactly like a scenography. Specifically like the one that Erich Kettelhut made for Fritz Lang's Metropolis. The influence of the German film5 on Otomo is undeniable. A few years later he even wrote the script for a movie with the same name directed by his friend Rintaro.

High-tech6, art deco, praire house, post-modern, a hint of Syd Mead and certainly futurist influences can be identified in the skyscrapers of Neo-Tokyo. Otomo mixes distant references and gives shape to something never seen before.

If we focus on singular buildings it is also possible to find more “on-point” references.

The humongous Neo-Tokyo Military Hospital is clearly a glazed skyscrapers under steroids, but it is also conceptually similar to the (already seen) Niban-kan by Minoru Takeyama: a series of simple extruded volumes connected to form a massive building. We can say that the Neo-Tokyo Military Hospital is a sum of the buildings born in that period, with a side similar to the Shinjuku Sumitomo Building (1974) and diagonal grafts similar to the Niban-kan.

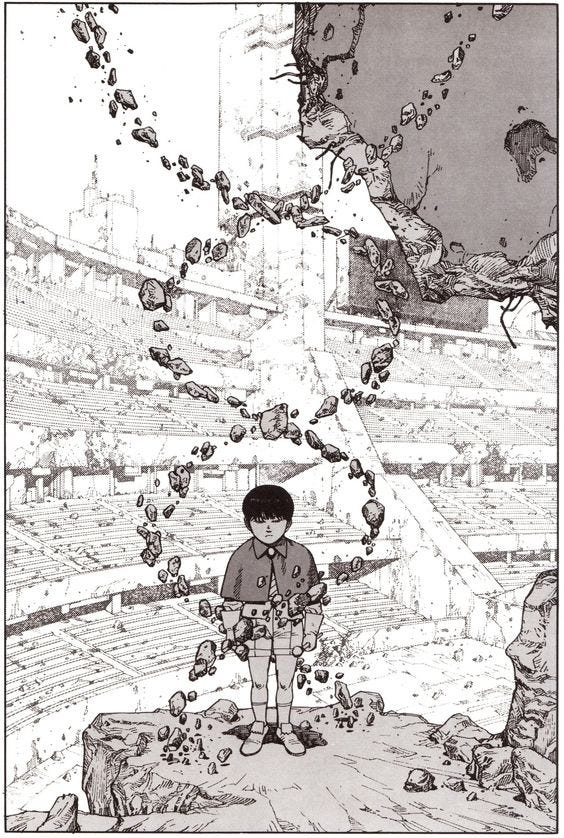

The Neo-Tokyo Olympic Stadium is, on the other hand, a direct reinterpretation of the (today demolished) Tokyo National Stadium. Built in 1958 for the Asian Games of the same year, the stadium saw its capacity augmented to host the Olympic Games of 1964. The project by Mitsuo Katayama has the feature of being extremely horizontal. The seats have more room in front of them compared to modern stadiums. This horizontality and its classic aspect are easy to find in Akira’s Neo-Tokyo Olympic Stadium. Otomo (or probably his assistant Satoshi Takabatake) gave to the stadium a more “2019” look, with a massive concrete structure defining the inner partition and a sharp tower overlooking the olympic flame.

In a bird’s eye view it is possible to see the stadium under construction inside an Olympic area where a building similar to Eero Saarinen’s Ingalls Rink rises.

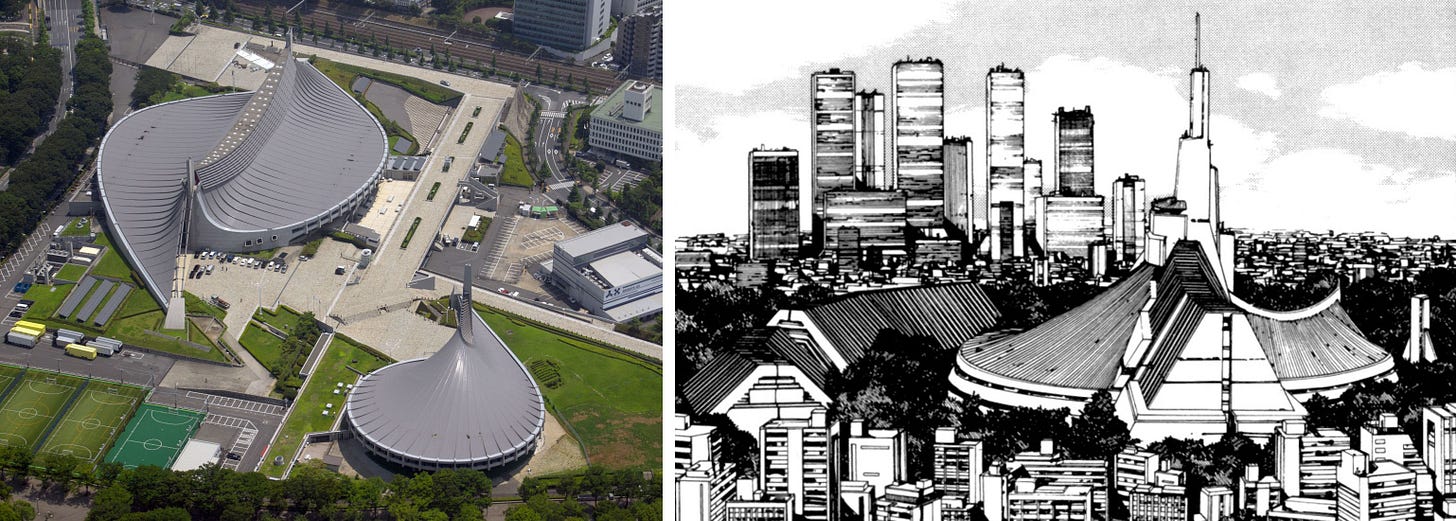

Sticking to Tokyo’s 1964 Olympics we can find another huge influence on Neo-Tokyo’s architecture: the Yoyogi National Gymnasium. The famous venue projected by Kenzo Tange is one of the masterpieces of modern japan architecture (if not THE masterpiece).

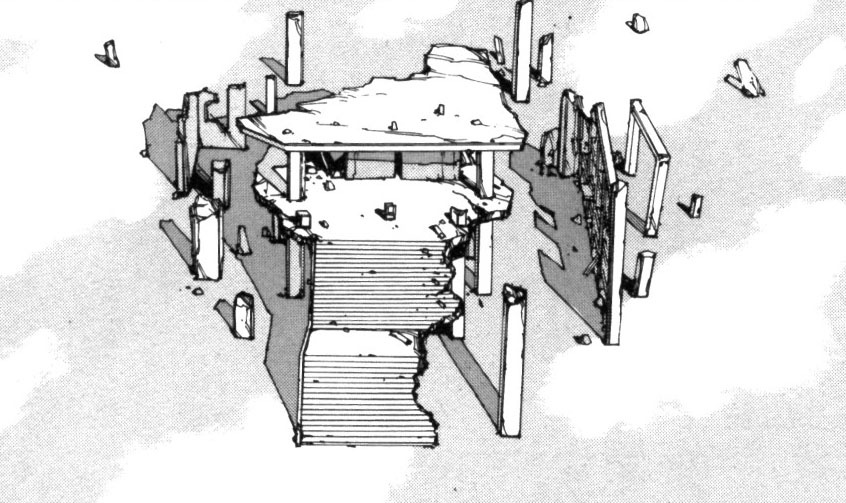

The striped surface of the roof is exactly the same of Lady Miyako’s Temple. Concrete grafts give to the whole building a futuristic look.

So at this point we can easily say that Neo-Tokyo is nothing but the actual late-70s Tokyo scaled to a massive and bold size. Every feature of the real Tokyo is exaggerated to convey the idea of unstoppable urbanization and dehumanization of the individual.

But again, that is nothing that blossoms out of the blue. How is possible to control in a dramatic way such a complex urban scenario?

The answer to the last question can probably be found in the previous long manga by Katsuhiro Otomo: Domu (1980). The setting is a massive Danchi (highrise residential building) that gave the chance to Otomo to experiment with complex urban scenarios.

After reading Domu, Akira seems a direct consequence (at least under the representation of architecture point of view). After Domu, Otomo understood how architecture could really shape the development of a story, so he molded his Neo-Tokyo as a sharp and endless scenario, where exaggerated buildings bundle upon each other until they are completely destructed.

An ongoing research

Time for a close. Let’s list some things that are quite relevant and that help us understand the role of architecture in Akira.

1. It’s absolutely fundamental to point up the fact that most (if not all) of the backgrounds from Akira were produced by Otomo’s assistants.

The most relevant of them, that also build a solid career on drawing backgrounds, is without doubts the aftermentioned Satoshi Takabatake.

You can follow him on Twitter at this link. He is a bike enthusiast and sometimes answer fans when asked about the works that saw his involvment.

The other major assistants were Yasumitsu Suetake and Makoto Shiosaki. At this point of my research I don’t know yet what was their exact role. I only know that Suetake was the Chief Assistant, so he would probably interact with Otomo a lot more than the other two. Takabatake became chief assistant let’s say around the last quarter of the manga, with Satoshi Kon joining as additional artwork7.

2. I recently co-wrote a paper where we tried to reconstruct the development of the Tsutsumi Danchi, the setting of the aftermentioned Domu. Makes a great couple with today’s newsletter in my opinion, reconnecting the dots that led to the representation of architecture in Akira. Give it a look.

3. Akira fanbase has great moments of sharing but also (sometimes) an elitist attitude. In this list below I try to link the places where is possible to find great info on Akira (and Otomo) in the hope to create a virtuous circle on the circulation of informations about Otomo’s work.

Apple Paradise: Omnicomprehensive archive of Otomo’s work by Jun’ya Suzuki. On his twitter he regularly posts about Akira and Otomo, his posts are full of juicy infos. Totally in japanese (thanks google translate).

ChronOtomo: A website listing all Otomo’s work in chronological way. Pretty fun to browse.

Akira and Katsuhiro Otomo Appreciation Page: One of the last great things happening in that trashbin known also as facebook. Otomo fans are sharing great images, their collection and sweet informations (sometimes). It really seems like a 2010 facebook group, collaborative and sane.

Otomo Zenshu: Official twitter profile dedicated to the brand new collection Otomo Complete Works. Otomo himself sometimes reply to the tweets of the fans.

Exploring Akira: another interesting blog.

Inu1941-1966 was also a great source of material but it seems to be down.

Eventually one day there will be an Otomo encyclopedia able to fill all the gaps.

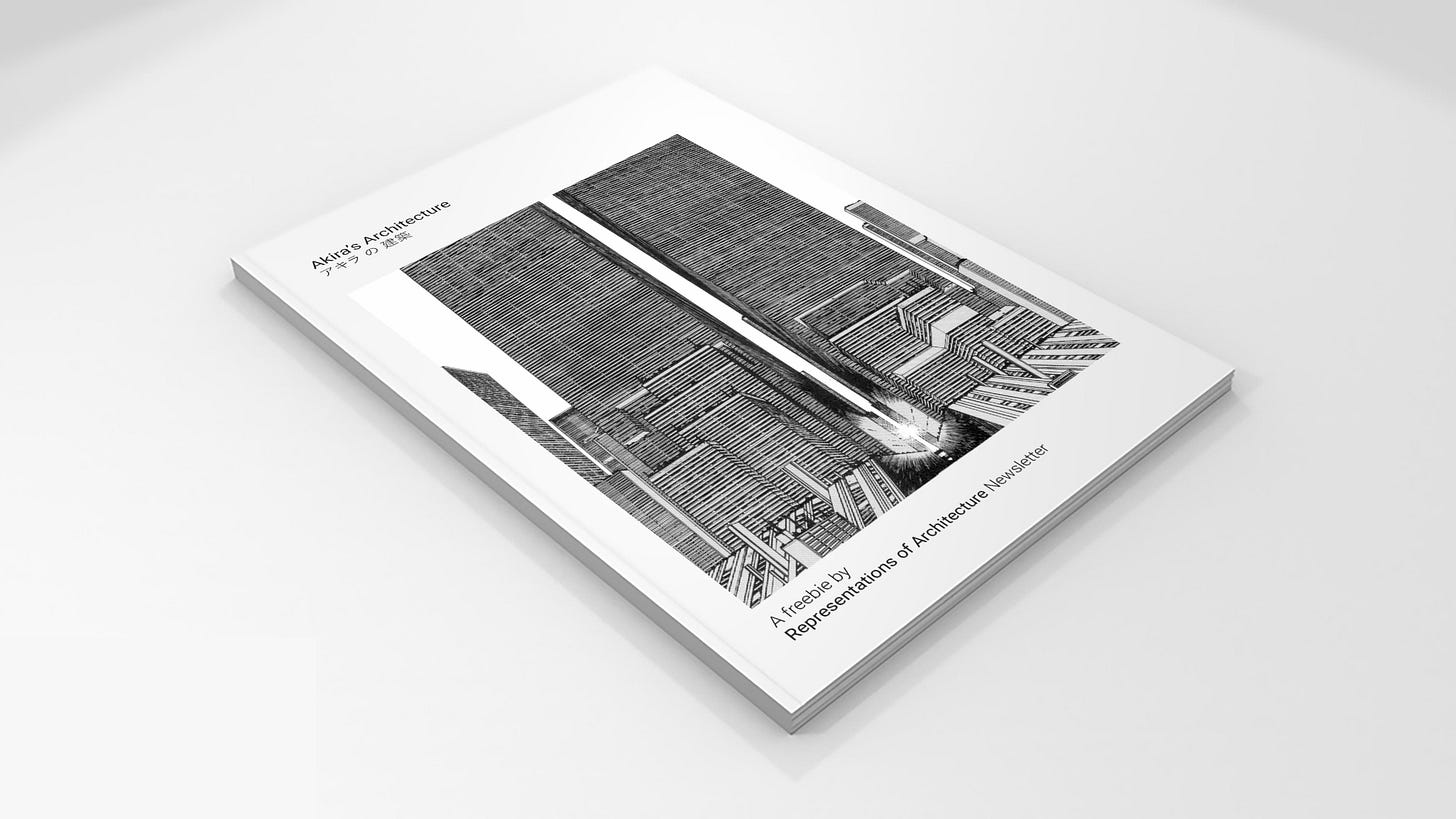

Akira Architecture: a freebie

For Berserk’s Architecture I asked you to share the newsletter to receive the pdf. This time I will not do it. You’ll find the pdf (at a decent resolution) at this link. If you want the high-res version just answer to this mail (or comment below if you are on Substack) and I will send it to you.

The result of the harvest and aggregation of all architectures contained in Akira is, in my opinion, something extremely interesting. It is like a mute comic, telling a story just by the progressive destruction of the buildings depicted. A visual experience that I recommend you to try, especially if you have read the manga.

I hope you are now curious about Akira. Maybe you want to read it… well there are different options. The unethical one would be to search some scans on internet, but probably the smartest thing you can do is buy this great 35th anniversary edition (complete with the amazing artbook Akira Club).

Fiuu… 😮💨 I think that’s enough for this week.

See you next saturday with a fresh new takeover. Don’t forget to like, share, blah blah blah…

CIAO,

Federico

I wrote about it in a past newsletter.

The curious thing about the manga is that was serialized for 4 years before being stopped to allow the conclusion of the movie. The publication of the manga was then started again in 1988 once the movie was released. Manga and anime share part of the story, with the former having a slightly different finale and a whole additional story arc.

Carola Hein and Philippe Pelletier in their Cities, Autonomy, and Decentralization in Japan (Routledge, 2009) wrote: “In the 1960s, urban redevelopment projects designed to transform the ward area of Tokyo into a high-density city were promoted within the Existing Urbanized Area. Under this policy, new systems for high-density land use were established. One example was the Super Block Development System (tokutei gaiku seido) of 1961; another was the Floor-area Ratio Regulation System (yosekiritsu seido), which regulated building volume but not height. It was brought into effect previously in Tokyo in 1963, and the Kasumigaseki Building [the first skyscraper in Japan, ed.], opened in 1968, is the first high-rise building with a height of more than 100 meters. This Floor-area Ratio Regulation System was fully brought into effect with the abolishment of the absolute height limit of 30 meters and the change of both the City Planning Law in 1968 and the Building Standards Law in 1970. These new systems paved the way for the construction of high-rise buildings more than 30 meters high.”

And obviously of the loose Tezuka’s adaptation from 1949.

In this sense it is clear how the Osaka Expo 1970 set a new standard in terms of technology. Showing to Japan and to the whole world what architecture could be. If you are curious there is an entire YouTube channel dedicated to it. This is the opening ceremony (skip to minute 46 to see Isozaki’s robots).

Other gaps of this research can be find in the perfect timing when the assistants joined the office. James Harvey, great comic artist and an Otomo connisseur, produced a timeline listing all of the japanese master’s work. It’s impossible to find it online, but if you ask him directly maybe he is willing to share it. James Harvey is also behind one of the greatest homages to Akira ever made: BARTKIRA.